At play with Andy Goldsworthy

Left to right: Andy Goldsworthy, Michael Dewey (mason), Alexa Kelley (head of material logistics), Devin Connor '12 (chief mason).

By Devin Connor ’12

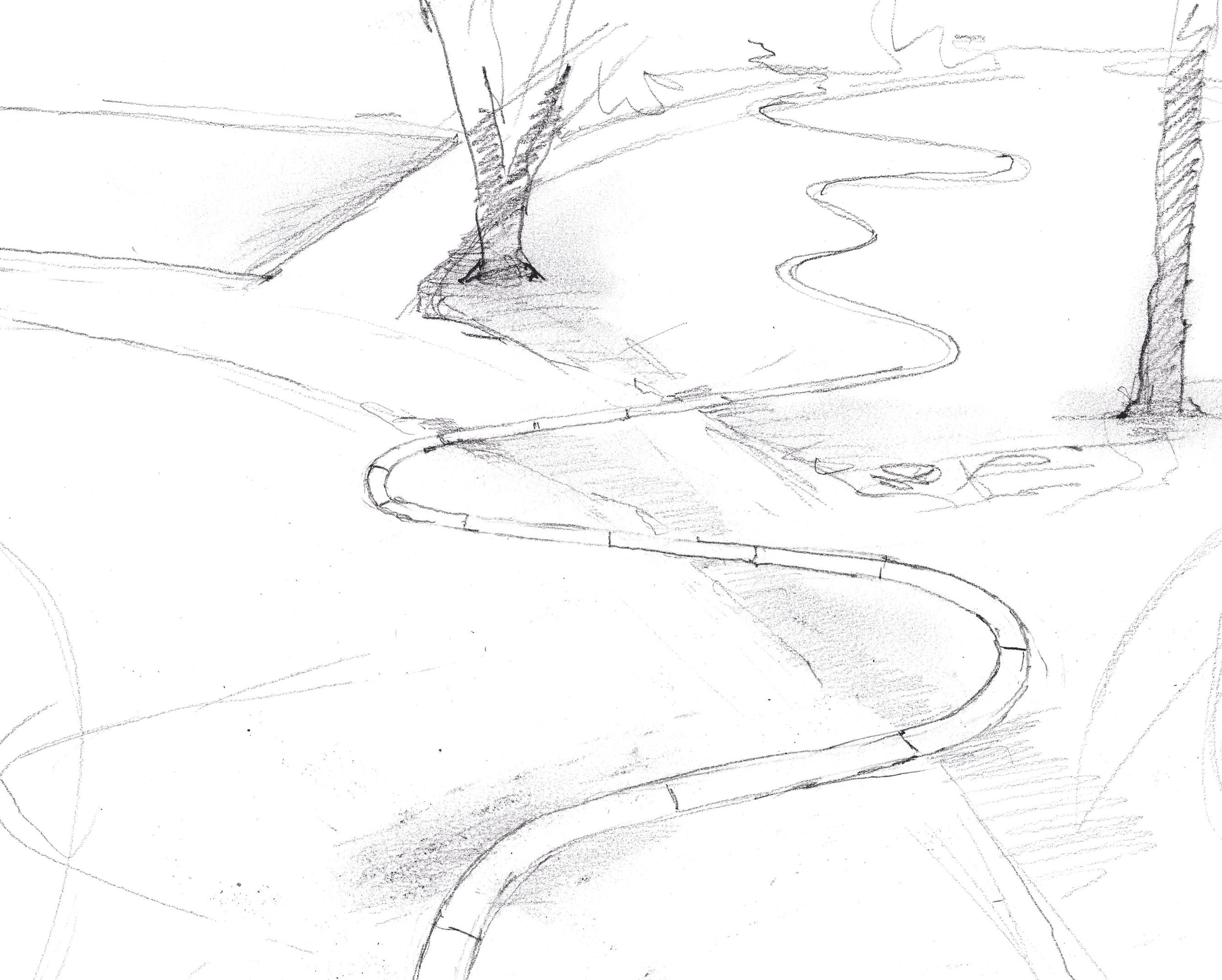

Our introduction was marked by a modest handshake and a brief exchange of glances. Unassuming in attire, his daily uniform consisted of monotone tan workwear and a sunhat. Like a caricature of neutrality, his appearance revealed nothing of his person. In the earliest days, he worked on preliminary layouts for the line alone. A quiet enigma in the college landscape, he carefully pulled lengths of hose into graceful curves, the indifferent subject of many a passing gaze. The unpretentious figure in tan worked at his strange labor with the slow and steady intent of a tradesman. It was all very obscure at first, Andy and the project. The process was yet to be developed, as was the shape and trajectory of the line itself. We might mock it up in stones or simply follow the curving hose. As local crews worked on preliminary stone cutting and I on basework and logistical concerns, my nerves mounted to a crescendo sensing the impending moment when curb would meet earth—the moment of inception. During the setting of those first few stones we played with excited apprehension. As I delved into my element, so did Andy into his. Within 20 feet of laying the winding curbstones, a notion of the art piece emerged. Along with that, from first stone to last there evolved a method and series of refinements that would express that notion gracefully.

Andy's greatest personal impact has been to awaken me to the sanctity of process.

The work and the process were grueling. These days, the curbs lining our roadways are set in concrete. Like everything in the modern world, the process has been systemized to increase production and limit the need for skilled labor. There is no question of what direction the curb will take; the curb follows the road. Not so with the obscure curb line that we would chase. We set our curbs into crushed stone with a three-foot hammer and exuberant force. The effort needed to set each curb to the desired height was immense. The ground would shake 20 feet away with the force of hammer meeting stone, only to drop the curb by a paltry fraction of an inch. Each stone was painstakingly cut, and the ends prepared to ever-more-nuanced specifications before being cut again during setting for a precision fit. The process required a great effort, and, with bloody knuckles and anguished bodies, an even greater focus.

Curved granite waiting to be set.

Goldsworthy with Dru Colbert's Installation Art: Activating Spaces class.

Line was an excruciating undertaking for all involved, perhaps none so much as the artist himself. There was an unrelenting sense of conflict between the needs of the art piece, landscape, and community. Not to mention the budget, timeline, and the pursuit of form. We faced valid concerns regarding tree protection, accessibility of road crossings, and use impacts. Andy had a clear desire to respect and encourage human engagement with the piece, open to input of how it might inhibit or enrich the experience of different beholders. But the challenges would become more abstract as judgements that questioned the piece’s value were brought to the surface. One protest chalked on a stone read, This is not human ecology. I've often wondered what fed this notion, and if the faceless judge anticipated the haunting feeling their protest would impart. As if to soften the blow, another of the writings insisted, We respect Andy. The laboring masons who discovered the messages wondered if that respect extended to us. And yet these challenges (and challengers) steered the project as components of a greater ecosystem affecting its articulation. The form of the piece was guided as much by the cooing, roars, and migration patterns of humans on campus as by the more conspicuous undulation of landforms. As a mechanism for bringing about Andy’s vision, I began to recognize the work as existing within this greater context. The many voices and forces weighing on us were inadvertent forces of nature acting on the formation of the art itself.

The work is the result of a process of engaging with context in the deepest sense, in landform, material and culture. He absorbs every bit of context—the history of local quarry workers and curb setters, the nuanced landforms of the campus, the tides, creatures, and very soul of the place.

From my position as head mason, there was a freedom to behold the project in a way truly distinct from my experience at the helm of creative work. I was able to surrender to the process, trusting the governance of form to our leader. This was the meat of the project for me, existing in the realm of this dichotomy between the perceived art form and the physical process of creating it. Set in the landscape, the sculpture appears effortless, as if its form was ordained in the natural order of things. In reality, it is anything but. Only through massive effort could we create this thing whose beauty relies entirely on its perceived effortlessness. Focusing on art itself while actualizing it through a physically intense and masochistic process was revelatory. Working with Andy as he toiled over the form, our small installation crew soon found ourselves in fluent accord: This stone isn't the right radius. This whole run needs to be taken out and reworked. What began as a concept in Andy’s mind became this living thing whose needs we could sense intuitively and provide for enthusiastically. Despite the physical cost of manipulating these unforgiving materials, we were acutely aware of something sacred in this process and so would never think to protest. What a gift, to wade through this chaos and toil, and to find amongst our core crew a singular focus on that sacred point which, through its carefully controlled meandering through the universe, constituted the artwork.

Andy's greatest personal impact has been to awaken me to the sanctity of process. After a life of putting so much concern and ego into finished work, this project leads me to believe that it is the action of engaging the universe in expression which aligns the artist with something essential. Andy appears to spend the majority of his life nurturing this phenomenon, embracing the pulse of creation through near constant immersion and expression of it. Throughout the project he would disappear in quiet moments to the shore to create ephemeral works. Some were in keeping with what you might imagine— arrangements of stones and organic ephemera. Others went deeper. He did a series of recordings burying himself in seaweed, plunging blindly into the bugs, crabs, and other life as the tide crashed in for nearly an hour.

The line in the landscape.

In working with Andy, the disembodied notion of the human and nature that plagues the modern perspective is resolved. Andy, adrift in the seaweed, can hardly be abstracted from nature. He rejects being asked to “design” in the human realm, refusing to manufacture context for his own work. He is not the arbiter or architect of the world his art occupies, but a creature whose engagement with the world results in art. The work is the result of a process of engaging with context in the deepest sense, in landform, material and culture. He absorbs every bit of context—the history of local quarry workers and curb setters, the nuanced landforms of the campus, the tides, creatures, and very soul of the place. With this immense sense of place he sets his intention, engaging in physical process as a conduit for the expression of something universal.

In the end, I’m left with a growing sense that this yearning we all have to create as individuals is connected to something essential wanting to be expressed. After years of unrelenting seriousness in my own work, it is Andy’s playful engagement with the natural world which inspires me. His work is an extension of the care he gives to his own soul. As he baptizes himself in the tides of nature, it becomes nearly impossible for his artistic expression to avoid revealing some natural principle. In a sense, Andy is an artist by species, and his artworks are the footprints left from his deep and unconventional engagement with his environment. As I sit in reflection, months on, I look to my masons and see a similar principle expressed. While burdened by perception of our class and creed, we too spend our days chasing lines through space, leaving tracks and traces that look an awful lot like art.

Andy Goldsworthy's 1,500-foot-long Road Line (2023) is the artist's first permanent installation in the State of Maine. Devin Connor '12, founding owner of The Garden Artisans, served as chief mason on the project.

Edited by Alexa Kelly

Concept drawing by Andy Goldsworthy.