Just doing my part

Ursa Beckford ’17 interviews US Rep Chellie Pingree ’79

Representative Pingree in Acadia.

With a new administration comes new challenges and new opportunities. What does it mean to work in government after the challenges of the last administration? For US Congresswoman Chellie Pingree ’79 it means remembering your roots while becoming chair of the House Appropriations Committee Interior, Environment, and Related Agencies Subcommittee, one of the most powerful positions in Congress. Ursa Beckford ’17 brings us this insightful interview with the congresswoman.

Ursa Beckford: To start off with, what are you focused on right now? What makes you get up in the morning?

Chellie Pingree: Well, as a member of Congress, every day is a little bit different. One of the challenging, but wonderful, things about this job is you wake up in the morning and you’re often facing a day completely different from the day before. We do everything from deal with challenging constituent issues to internal debates and negotiations within our own party. We have committee meetings and hearings, we’re working on bills, we’re voting on the floor. But overall, I’ve always worked on some of the same themes. I’m an organic farmer in my other life, so everything about farming and food systems has been at the forefront for me. We’re doing a lot of work on climate change and its relationship to agriculture. So I’ve been focusing on those issues in the infrastructure packages we are working on right now.

Similar to how it was framed in the Green New Deal, you can’t just talk about environmental issues and leave out people. It can’t be just about the environment. You have to think about environmental justice and then you have to think about people’s everyday lives. How do people get to work? Do they have childcare? Do they have health care? Are their own lives manageable and healthy? Do they have housing? Really, the things that people confront every single day in Maine. So I think I always look at it through that lens. How are we going to do this and make sure we also are thinking about people?

When people ask me about human ecology, I tend to say, It’s not just a funny degree with a complicated name… It’s actually how you take some of these science-related issues and think about them from a human perspective.

UB: That’s fascinating, because I think human ecology is often defined as the study of the relationships between humans and their natural or social environments, meaning someone might focus on one or the other. But you see them as integrated.

CP: Yeah, part of the difference is that once you’re out of college you’re trying to implement what you learned... So you have to think about everything.

Representative Pingree at the dedication of the Congresswoman Chellie Pingree ‘79 Greenhouse, part of the COA Davis Center for Human Ecology.

College of the Atlantic

UB: How does COA continue to influence you?

CP: You spend a fair amount of time in college and you learn things that you don’t know you’ll use until much later in life. I learned a lot of different things that still impact my life. I even took a couple of business classes, I took basic bookkeeping. I don’t know how I snuck that class in, but I’ve run a small business most of my life, so I still lean on a lot of that knowledge.

I was at COA the other day. They were opening up the Davis Center for Human Ecology, and I was very excited because it’s such a green building and my committee oversees the Forest Service budget, so I’ve been interested in funding a lot more forest product innovation. One of the things about that building is they used wood fiber insulation, a new product that’s going to be made by GO Lab, a company in Maine, using a German technique to repurpose wood byproducts into environmentally friendly insulation material that is really efficient.

We’ve had somebody from GO Lab come and testify at agriculture hearings to talk about how to have a sustainable forest and how a product made out of wood holds onto carbon, which then stays in the building and becomes a carbon sink for a long time. I think this was the first time that they’d used wood fiber insulation in a building on a large scale, and it’s at COA. So it’s nice how it all tied together for me. COA is doing a lot of really great stuff that is topical for what we’re working on today. I feel really connected to the things happening at the college.

UB: What was it like to be back on campus?

CP: I found myself talking to another alums and saying, When I was here, it was before this building burned down... And I sort of felt like one of those really old people who’s like, Yeah, in my day we only had one building...

When I first got there in the 1970s, we didn’t have on-campus housing. There was just a weird little motel down the road they rented for students… It was like a horror movie motel. You could share a tiny, gross, smoke-filled room with a roommate. So very quickly a couple of my friends and I found a place to rent in town. Today, I feel like I’m talking to people who can’t even conceive that it was the same college when I was there. But I just love the fact that it’s grown, it’s become a college with a lot more resources and more opportunities. It’s great.

UB: How has human ecology influenced your life and work? I imagine you’re the only powerful congresswoman with a degree in human ecology. Do you notice that you bring a different perspective?

CP: I’m sure I’m the only congressperson who has this degree. I think it’s a combination of that degree, but also coming from Maine, where I don’t think people separate the natural world from our daily lives as much as you might in some other places. You can go up to anybody in Maine and start a conversation about the weather. When you live in a rural area or area impacted by weather, people talk about it all the time. And that may seem incidental, but it’s a reflection of the fact that people pay attention to what’s going on outside. A lot of Mainers are much more aware of things like, Have the trees changed? What season are we in now? A huge percentage of Maine people burn wood to heat their houses. They have a garden in their backyard. They can’t wait to get outdoors, whether they’re hikers or hunters or cross-country skiers. Some people really like going fishing or being on lakes… That’s always given me this perspective that everybody has an equal amount of concern about their lives because their lives are rooted in nature.

Back to the Land

UB: Did you bring that human-ecological perspective to COA, or did it develop there, or later on?

CP: I chose COA because it was a college in Maine that represented some of the things that interested me, but it wasn’t as if I grew up in life thinking, I want to be an environmentalist. Before I went to COA, I had been living in Maine for a couple years and was a back-to-the-lander, which really hadn’t been my plan in life either. I grew up in Minneapolis, went to an alternative high school in Massachusetts, and then followed a boy to Maine. I was reading Helen and Scott Nearing’s books, and I decided it was something that made a lot of political sense… It was a way to differentiate yourself from what the establishment was doing. We had a government we couldn’t trust, sending our friends and siblings to Vietnam, and you had to live a life to show that you were protesting the status quo. So even though I didn’t know much about how to run a wood stove or can tomatoes or anything, it just somehow all flowed.

So I guess I brought all of that to College of the Atlantic when I got there, and it colored what I wanted to study. I wasn’t interested in going to a school where you had a lot of required classes that you had to take… I was sort of done taking classes the way I had in high school. Being able to focus on what I wanted to do and figuring out how all those things fit together was pretty useful.

UB: So it seems like your views on human ecology are really related to your core interests in Congress and they go back to those early days.

CP: When I was at the college, I mostly focused on growing things, growing plants. Eliot Coleman, who sort of became the guru of organic farming, taught a few classes... I instantly gravitated to being a farmer, having an organic farm, living a rural life.

By the time I ran for the House, I had, one way or another, either been a gardener or had a small farm, or had a small business related to farming, all my life. I served for eight years in the Legislature, where I focused more on health care, prescription drug prices, things like that. When I got to Congress, there were a lot of members who were very focused on health care, and it’s a big national issue. That’s when we passed the Affordable Care Act. But I literally found no one who was interested in food systems. There were a few people who supported organic farming, but it wasn’t their issue. So that really was when I just dove in and said, look, I know so much about agriculture, organic farming, the changing consumer market, what people want to buy, what they want to eat, what they want to feed their kids, toxins related to the environment—all those things. I was like, This is a void and someone needs to do this.

UB: What do you think your younger self would’ve said about you coming to serve in Congress? It’s interesting to hear about your earlier views on government, and here you are.

CP: Well first off, I literally had never engaged with the political process in terms of whether I was a Democrat or Republican, or how political parties worked, until a few months before I ran for the Legislature in 1992. I always voted, but I paid very little attention to it all. I’d never gone to a party meeting. And certainly when I was a teenager, I felt very alienated from government. I didn’t engage in it.

I really started to get interested in the process of governing on a local level because I live in such a small town. We have a town meeting every year in March, a form of government in and of itself. The entire town fits into a big room and takes a vote on every line item in the budget. And it really got me thinking much more about how the system works, how we govern. You weren’t abstracting it because you think about it all the time. You talk to people in your town about it… You don’t think, Oh, that’s government and it doesn’t connect with me. It’s more like, What do I want to have happen in my future, in my kids’ future?

Eventually I was a tax assessor, then a planning board member, and then I was on the school board. That got me thinking about how you get the five people on the school board to agree about what you think is important for your kids. So I came into government and got comfortable with it in a totally different way.

I don’t like all the chatter that goes on every single day about whether the Democrats are going to make a mistake here, or what about the strategy of this or that issue…

UB: So you’re not reading Politico every day.

CP: [Laughs] I have to read Politico every day because I need to know what’s going on, but when several reporters call me to ask, What do you think Senator Sinema will finally do? I’m kind of like, tomorrow will be different from today, a week is a long time in politics, and I can’t get agitated. You have to understand that sometimes you’re a cog in a wheel and, yes, you might have a lot of influence, but you also just have to do your little part every single day. So that’s what I do, I just keep doing my part.

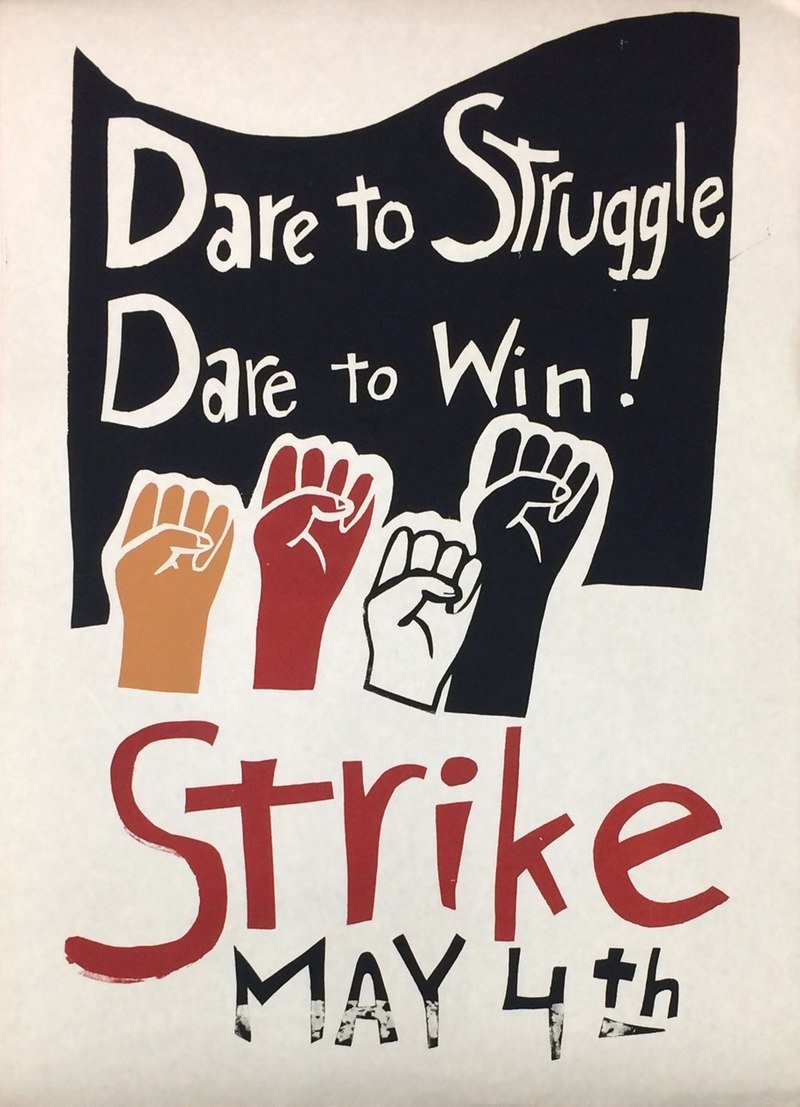

Kent State poster from May 4, 1970.

World Changing

UB: I think it’s fair to say that people don’t have much faith these days in the government’s ability to deliver, solve problems, or to work together. Thinking of COA’s motto, “Life changing, world changing,” in this particular moment—with the pandemic, George Floyd’s murder, climate change, withdrawing from Afghanistan—what are your thoughts on world changing? How do we proceed in this environment? How do we move things in the direction that we want to see them go?

CP: There are some days when I think, A week is a long time, and things may look very different next week. At other times, I wonder if people will look back in 50 years and say, This was the decline that led us to bottom out and ruin civilization. Honestly, I don’t know. So again, I just have to get up every day and think, I’m going to work on my part. I’m going to do my best to keep the system moving.

We do have a lot of big things that we’re really worried about—how voting rights are going to work out in the future, the age of disinformation and misinformation, climate change, the gap between the rich and the poor, how people are surviving in the pandemic. I don’t want to make light of any of it, but every once in a while, I’ll watch a documentary on the 1960s, because it’s hard to remember exactly how you felt 50 years ago. I’ll see the students being shot at Kent State and all the civil unrest. In that era, we thought we were living through a failure of government and things were never going to come back together again. We thought there would never be a president we could trust. Young people then were just as disaffected from government as some people feel today. Sometimes it’s hard to tell, but I’m not sure if we’re in the worst era we’ve ever lived through.

UB: Are you in the thick of cajoling your colleagues about the President’s agenda? What does that work look like?

CP: My work is about being well informed about exactly what’s in the package, what its impact will be, what the statistics are around it. I’m doing everything from lobbying the speaker on why this is important, to working with my colleagues in the Senate who also focus on agriculture issues… And then because some of the climate change policy is in flux and because this or that senator doesn’t like the Clean Energy Plan, there might be some more openings because if we cut out that section, then we’re going to still try to reduce emissions. So I’ve been talking to my environmental colleagues who are in the negotiations, because sometimes people don’t understand how you can reduce emissions through good agricultural practices that sequester carbon. It’s the whole spectrum from policy to personalities, talking to people, talking to the administration.

UB: What do you think of civility? You don’t seem like someone who pulls punches. But I think there’s this interesting question about whether civility is a dirty word. Is it important to be civil, or does being civil mean we’re not speaking the truth, or speaking truth to power? I’m curious where you land on that.

CP: Well, I’m a strong believer in civility. I’ve lived in a small town my entire adult life, and you can’t get along with your friends and neighbors in a small town if you’re always picking a fight or telling somebody what you think. You don’t walk up to people and say, I saw you got a Trump sticker on the back of your car, so you’re not coming into my house to do the plumbing… It just doesn’t work like that. Your kids go to school together. I live on an island, so we ride on the same ferry. All my life I’ve had to get along with people, it’s part of survival. It’s part of human nature.

We don’t want to be in a constant state of conflict. And I don’t know that I’ve ever met a person I didn’t agree with on something. Sometimes I’ll have my knitting or handiwork on the plane, and people will talk to me about that. And I’m sure some of them hate me, but they’re like, Oh, my grandmother uses the same kind of yarn.

Civility was meant to be built into our political system. That’s why we have parliamentary procedure or Robert’s Rules of Order. That’s why when you get up and speak in the Maine Legislature, you say, My good friend, the gentleman from Knox County. Those things might be a little bit of fake civility, but they’re partly to keep the temperature down and keep the argument to the argument, not to the personal attack. It’s one of the things that in some ways has started to become a norm in our country, so I feel like civility goes hand in hand with governing.

Tomorrow Will Be Another Day

UB: Any moments on the other end of the spectrum? Moments in the course of your work lately that gave you hope or made your week?

CP: Sure. I mean, honestly, I can’t tell you how hopeful it’s felt being able to work with a brand-new president... It’s a completely different world. You get to talk to people who are professional and competent and eager to do their jobs. And that’s true at the National Park Service or at the Veteran’s Department or wherever you are. I feel very hopeful working in an environment where in spite of all the politics of will we get it done or not, we’re working on one of the biggest transformational agendas that I’ve been able to work on during my entire time in Congress. This is way bigger than anything we did in the Obama administration. We won’t be able to accomplish everything because that’s the nature of politics, but I feel great about what we get to work on every day and it’s a completely different world from the last four years.

UB: That’s great to hear because I think it’s the political headlines about whether the president is doing a good job or the latest poll out of Iowa that we often latch onto.

CP: Yeah. I mean poor President Biden. In my opinion, he doesn’t catch a break. The guy’s working hard. He’s compassionate. He cares about his job. He’s putting forward big agendas. Everything’s not going to go his way. He’s dealing with this pandemic, a 20-year war in Afghanistan, recalcitrant members of Congress. But he’s a decent guy… every day, trying to do the right thing. It’s always portrayed in the media as, Oh my God, the nation just lost faith in him, but, like I said earlier, you just have to close your eyes and say, Tomorrow will be another day, we’ll just keep doing it.

Editor’s Note: Since this interview was conducted, President Joe Biden signed the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act into law on November 15, 2021.